OPERA

Santa Fe Opera

The Crosby Theatre, Santa Fe

RODNEY PUNT

Santa Fe Opera

The Crosby Theatre, Santa Fe

RODNEY PUNT

Samuel Barber’s first opera, Vanessa, began life promisingly in 1958, debuting to rave reviews at the Metropolitan Opera. Some critics regarded it the greatest American opera to date and it soon earned a Pulitzer Prize. But a poor subsequent reception at the Salzburg Festival prompted Barber’s revision, after which changing musical tastes and the culture wars of ensuing decades left it neglected.

If one knows only the Barber of his exquisite Adagio or nostalgic Knoxville, Summer of 1915, the muscular score and bracing theatricality of Vanessa will come as both a surprise and a revelation. Santa Fe Opera General Director Charles Mackay accounts it an “unquestioned masterpiece of the mid-twentieth century" and this reviewer agrees. On July 30, in the sixtieth anniversary year of the company (a span of time equivalent to the life of this work), Mackay gave Vanessa its company premiere. It was worth the long wait.

If one knows only the Barber of his exquisite Adagio or nostalgic Knoxville, Summer of 1915, the muscular score and bracing theatricality of Vanessa will come as both a surprise and a revelation. Santa Fe Opera General Director Charles Mackay accounts it an “unquestioned masterpiece of the mid-twentieth century" and this reviewer agrees. On July 30, in the sixtieth anniversary year of the company (a span of time equivalent to the life of this work), Mackay gave Vanessa its company premiere. It was worth the long wait.

Anatol (Borichevsky) and Vanessa (Wall)

|

The setting is an unspecified "Northern" country with the period feel of an Ingmar Bergman film or Hollywood melodrama of the 1940's. Its noirish libretto was penned by Barber's life partner, Gian Carlo Menotti, and teems with a psychological verisimilitude influenced by their own long and complicated relationship. Quasi-Freudian undercurrents involve trade-offs between an individual's unshakable ideals and the world's compromised realities.

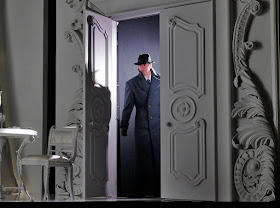

The action opens with a still beautiful Vanessa anticipating the return of her lover Anatol after a two decade absence. Awaiting his return, she has lived in a kind of suspended animation, with the mirrors covered to stop time. When Anatol's son, also named Anatol, arrives, he announces that his father died long ago.

Soon enough Anatol's wandering eye and caddish behavior set off a crisis in the household, as both Vanessa and her niece Erika fall for him. The latter’s brief affair ends badly, but a smitten Vanessa abandons her isolation to pursue life with the much younger man in Paris. A disillusioned Erika takes on Vanessa’s previous hermetic posture, ordering the mirrors to be covered again. Observers of the goings-on include the silent Baroness (Vanessa's mother and Erika's grandmother) and a tipsy, kind-hearted Doctor, who reveal their own poignant perspectives on life and love.

Soon enough Anatol's wandering eye and caddish behavior set off a crisis in the household, as both Vanessa and her niece Erika fall for him. The latter’s brief affair ends badly, but a smitten Vanessa abandons her isolation to pursue life with the much younger man in Paris. A disillusioned Erika takes on Vanessa’s previous hermetic posture, ordering the mirrors to be covered again. Observers of the goings-on include the silent Baroness (Vanessa's mother and Erika's grandmother) and a tipsy, kind-hearted Doctor, who reveal their own poignant perspectives on life and love.

The Doctor (Morris) and Vanessa (Wall)

|

Under James Robinson’s direction, Allen Moyer sets the scene in a claustrophobic, time-stopped home of monochrome whites and grays. In later celebratory scenes, with friends, family, and lovers, the set expands in a flood of light and pastel costume colors. The mirrors uncover briefly, only to shutter again as Erika takes on the hermetic role from a departing Vanessa.

Vanessa's emotional state moves from eerie waiting to eerie giddiness, a mental detachment from common sense that could limit audience empathy. Fortunately, Soprano Erin Wall finely gauged her role's journey and portrayed it with dignified conviction, never overplaying or making character into campy caricature. From her early "Do not utter a word, Anatol" she established just the right tone for the psychological safety-zone in which she dwells.

Erika (Virginie Verrez)

|

The role of Erika traverses a wider arc, from supportive niece to a predator's victim, later from failed interventionist to a dweller in her own twilight. One is reminded of the relationship of Mrs Havisham and Estella in Dickens' Great Expectations. (No wonder Maria Callas refused to create the role of Vanessa when she saw the arc of Erika's character.)

In her first act aria, mezzo soprano Virginie Verrez established Erika's vulnerability in the wistful "Must the winter come so soon?", followed immediately by the sharp expressionistic thrills of "Listen ...They are here" as Anatol arrives at the door. Sweet-voiced but strong-willed, Verrez made the most of her journey of many moods in the evening's stand-out performance.

Tenor Zach Borichevsky's Anatol was a proper cad, but not so much an evil one as an unsympathetic victim of behavioral fate to exploit female vulnerability. Bass-baritone James Morris, luxury casting as the Doctor, made the most of his role as the personification of empathetic wisdom when sober and old fool when drunk. Mezzo-soprano Helene Schniederman was an anchor of muzzled propriety as the Baroness who sees and knows all but utters nary a word. Bass-baritones Andrew Bogard and Andrew Simpson were, respectively, the Major-Domo and the Footman.

Conductor Leonard Slatkin’s precision-primed orchestra announced the arrival of a great work at the instant of its downbeat. Bracing brass and whistling woodwinds set an icy mood as the drama unfolded. In the revised three-act version mounted here, Vanessa's inspiration and dramatic tension never floundered.

The complex expressionistic score is an extension of the kind of advanced writing in Richard Strauss's Elektra and Hollywood's psychological thrillers, of which Bernard Herrmann's Vertigo is the exemplar. Yet the sound-world in Vanessa is unique, an object lesson in the integration of melody, harmony, orchestral color, and the kind of vocal writing that is a lost art in many works today. One marvels at the craftsmanship.

Conductor Leonard Slatkin’s precision-primed orchestra announced the arrival of a great work at the instant of its downbeat. Bracing brass and whistling woodwinds set an icy mood as the drama unfolded. In the revised three-act version mounted here, Vanessa's inspiration and dramatic tension never floundered.

|

| Chorus |

Though it was composed in the middle of the last century, there are those still living who remember Vanessa's 1958 premiere. For the rest, hearing it with fresh ears today, one need no longer be concerned with the stylistic vogues that had consigned the work too soon to its decades-long obscurity. Indeed, since Vanessa's composition, several musical styles have come and gone. The once dominant atonal school in America’s universities eventually passed into its own historical niche. Minimalism was born and, under composers like John Adams, matured into a more eclectic idiom. The Neo-Romantic style of a David Del Tredici made what had become old new again. In fact, today’s eclecticism provides aural space for audiences to listen for quality more than style.

Samuel Barber made of Vanessa a masterpiece beyond style.

---ooo---

Photos by Ken Howard

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.