REVIEW

Long Beach Symphony at the Terrace Theater, Long Beach Performing Arts Center

DAVID J BROWN

There are some large-scale repertoire works whose duration presents a programming conundrum: too long for an equal-length first half of one or more other pieces, but too short to fill the entire evening. Some Mahler and most Bruckner symphonies come to mind, as well as Brahms’ German Requiem and on a less exalted level, Orff’s Carmina Burana.

|

| Eckart Preu. |

To fill that slot before the LBSO’s grand finale to its 2018-19 season, Music Director Eckart Preu’s solution was novel: eschewing the usual fallback of either one of the short Beethoven symphonies or a Haydn (or like some more “challenging” UK programmers, slipping in a shovelful of unpalatable/forgettable/commissioned contemporary grit), he went instead for one of the preceding era’s grandest celebratory works, Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks HWV 351, composed in 1749 for outdoor performance to commemorate the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.

|

| Plan and elevation of the 410ft long, 114ft high, pavilion built for the fireworks display on 27 April 1749; the building on the right caught fire and burned down during the show. |

All in all this work was a highly successful choice. The sequence of grand, non-developmental French Baroque forms was sufficiently remote in style to complement rather than be dwarfed or emasculated by the symphony’s giant drama. Though the Kalmus edition Maestro Preu used reduces Handel’s original cohorts of wind, brass and percussion to three each of oboes, bassoons, horns and trumpets, plus one timpanist, his use of the LBSO’s full strings designedly ensured a rich amplitude which, along with plenty of vigor, and accurate, committed playing, made for a grand and anticipatory festiveness in the extensive Overture—though with an appropriately graceful stepping back in the brief Lentement for oboes and strings before the repeat of the movement’s main body.

|

| George Frideric Handel in 1742, seven years before the Fireworks Music, portrayed by Francis Kyte. |

Before the main course, Maestro Preu paid due tribute to the many who contribute to the Long Beach Symphony season: the audiences and sponsors, the Performing Arts Centre’s and LBSO’s staff and Ovation! volunteers, and especially the players, amongst whom he singled out the principal percussionist Lynda Sue Marks, retiring from the Orchestra after 62(!) years’ in its ranks (and who made her final appearance wielding the triangle as one of the three percussion players Beethoven adds to his already large forces in the symphony’s coda).

|

| Lynda Sue Marks. |

This was apparent right from the outset, where Preu was meticulous over Beethoven’s carefully qualified Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso (a “little” majestically?!), if not quite at the metronome quarter-note=88. Rather than the usual distant fog of bare-5th, the pianissimo opening on divided violas and 'cellos against sustained horns probably got as close to being audibly 16th-note sextuplets, as written, as was possible in the Terrace Theater’s acoustic, and led to a first fortissimo tutti as clean as it was explosive, establishing the drama, scale, and dynamic range of what was to follow, and enabled by the LBSO’s utterly committed playing.

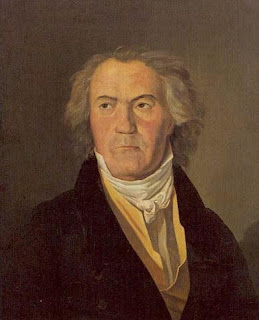

|

| Beethoven in 1823, when he was composing the Ninth Symphony, as portrayed by Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller. |

This did clarify the movement’s structure as a complex set of variations (which tends to get lost when it’s taken veeery slowly), and turned it into an idyllic interlude between the Scherzo—to which Preu and his orchestra had given a positively cosmic dynamism—and the Finale to come, rather than being a self-contained epic of sublime beauty. But inevitably the speed did smudge some detail in a later variation where the undulating string sextuplets became hectic rather than flowing; a little easing here would have made a difference.

(Just to get one other niggle out of the way—why wait until the break between Scherzo and Adagio for the four vocal soloists to come on? Though they made their way unobtrusively enough to the platform, the inevitable swerve of audience attention and applause was an unnecessary interruption after the cumulative power of the first two movements.)

The Finale got off to a slightly rocky start with a conspicuous wrong entry, so that Beethoven’s revisiting of the first three movements’ main motifs seemed a bit rattled rather than reflective, but once the (appropriately urgent) first statement of the famous “Ode to Joy” theme was under way on piano ‘cellos, the movement was set fair. From the basses’ first declamatory “Freude!” and throughout thereafter, the Long Beach Camerata Singers, reinforced with the UCLA Chamber Singers, were outstanding, rising magnificently to the succession of Himalayan challenges that Beethoven throws at his chorus, not least the sopranos.

|

| Soloists in action: l-r: I-Chin Feinblatt (alto), Kala Maxym (soprano), Jason Francisco (tenor), Steve Pence (baritone). |

Driven by shrieks from what sounded like more than the single piccolo Beethoven specifies, the final Prestissimo, though not overly headlong like some performances, was so electric that to reprise it, as they did when the torrents of applause finally subsided, seemed not superfluous but a necessary further discharge of the cumulative energy.

Orchestra and chorus alike covered themselves in glory, led with missionary fervor by Maestro Preu and (to judge by his enthusiasm when interviewed by Preu in the pre-concert talk) the Camerata Singers’ Artistic Director Dr. James Bass. Though there's no one "right way" to perform such an endlessly many-sided masterpiece as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and indeed some may have felt short-changed in terms of spaciousness and reflectiveness, for me this was one of the most sensationally urgent, coherent, and undutiful performances of the work that I can recall in more than 50 years of concert-going.

---ooo---

Long Beach Symphony Orchestra, Terrace Theater, Saturday, June 8, 2018, 8 p.m.

Photos: Performers: Caught in the Moment Photography; Lynda Sue Marks; courtesy LBSO; Royal Fireworks Pavilion: Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Beethoven: Wikimedia Commons; Handel: National Portrait Gallery.

If you found this review to be useful, interesting, or

informative, please feel free to Buy Me A Coffee!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.