|

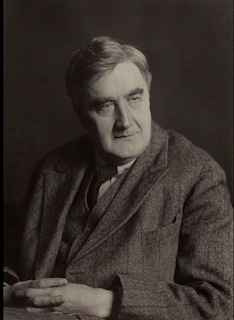

| l-r: Rachel Mellis, Martin Chalifour, Victor de Almeida, Todd Mason, Cécilia Tsan. |

REVIEW

Cécilia Tsan and friends play Beethoven, Mason, and Mozart, Mount Wilson Observatory

DAVID J BROWN

Five years and four seasons on from its inception in 2017 (2020 was wiped out due to Covid), the summer series of Sunday afternoon chamber recitals in the great Dome of the 100-inch telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory—brainchild of Trustee Dan Kohne and Artistic Director Cécilia Tsan—remains unique and absolutely maintains its sense of specialness.

The tortuous drive sets up the mood, demanding care and triggering awe as you hug the base of towering cliffs of fractured granite while trying to not more than briefly glance over at the vistas across the valley. Finally you arrive, more than a mile above the level of LA but still only a couple of dozen miles north-east of the city. Then the deal is sealed by the 20-minute climb from the car park, feeling the altitude but inhaling clean air while bathed in brilliant sunshine, with the great white Dome looming ever more prominently ahead.

And then once you’re seated inside the Dome the first impact of the music is startling in its plangent immediacy, heard at the close range dictated by the annular floor layout that wraps around the mighty telescope skeleton, protruding through from its supports on the level beneath. Yet by some miracle the extraordinarily resonant acoustic seems to have no downsides. The forte chords with which the 25-year-old Beethoven kicks off the opening Marcia of his Serenade for Violin, Viola and Cello in D major, Op. 8— the initial work in this first concert of the new season—were as cleanly transparent as they were impactful.

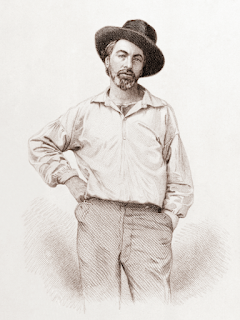

Beethoven’s five early string trios tend to be regarded by commentators as a minor-league warm-up for his great sequence of string quartets, and amongst them this Serenade gets even shorter shrift than its companions, Op. 3 and Opp. 9, due to its clear intent to be a relatively lightweight piece for domestic music-making. This performance, however, by Martin Chalifour (violin), Victor de Almeida (viola), and Ms. Tsan herself (cello), revealed a wealth of delights.

|

| The young Beethoven, by Riedel (1801). |

Perhaps most significant, though, was the group’s clear relishing of the young Beethoven’s humor, as when he caps the ensuing and otherwise brief and to-the-point Menuetto and Trio with an affectedly insouciant 10-measure pizzicato coda, throughout which the players beamed to its ever more etiolated conclusion. Similarly, they didn’t stint on energy for the stuttering scramble of a Scherzo section that Beethoven twice intercalates into the third movement Adagio.

Again, the affection of the group’s approach to the Allegretto alla Polacca (one of the Classical era’s few pre-Chopin polonaises) didn’t stop them making the most of the way Beethoven pretends, via a couple of whole-measure rests, to lose interest in the movement at its conclusion. Finally, in the theme-and-variations, Mr. Chalifour, Mr. de Almeida and Ms. Tsan respectively seized the individual opportunities that Beethoven builds into his first, second, and fourth variations for the violin, viola, and cello to shine.

The centerpiece of the concert was the public premiere of the Trio for Flute, Violin, and Cello composed in 2021 by Californian native Todd Mason—one of several fruits of his enviably productive Covid lockdown period alongside the String Quartet No. 3 (premiered recently in his own house concert series) and the soon-to-be-recorded Violin Concerto.

If you divide American “classical” music into a few broad and by no means mutually exclusive areas, Mason aligns with those composers (e.g. Barber, Copland, Mennin, etc.) who have maintained the European tradition of through-composed developmental music, as opposed to others (think Joplin through Gershwin and Bernstein to Jake Heggie) who have engaged more with theatrical and “popular” idioms, and—off in a different area—the experimentalists like Henry Cowell, John Cage, and Harry Partch.

Mason’s Trio, cast in his oft-used three-movement fast-slow-fast form, perfectly epitomizes his carefully wrought style, but in a performance as eloquent as that given by Rachel Mellis (flute) together with Mr. Chalifour and Ms. Tsan, there was plenty for the heart and soul as well as the mind to engage with. The outer movements—a tightly constructed Allegro Vivo based around an opening unison and downward-stepping motif for all three instruments; and a contrapuntal Presto with something of the Irish jig about it, led off by the cello—are very much the supporting frame for the central Andante.

This builds steadily from a cool interweaving of seemingly indeterminate lines—first on cello and violin and then flute and violin—which, when the cello rejoins, cohere into an increasingly vehement colloquy within which a repeated motif of a falling perfect 5th and rising perfect 4th is prominent, passing from instrument to instrument with growing emotional intensity. The cantilena reaches a pitch but then suddenly falls away, as if too much has been revealed, and the glacial drifting of the opening resumes. The Pandora’s Box of subjective feeling has, however, been opened, and the music rises to further expressive peaks, driven by the falling/rising motif, before it finally falls back to the solitary chill of the opening.

There is already a fine performance of the Trio to be enjoyed on YouTube, but this concert premiere in the Dome was a different order of experience—a little more spacious overall, perhaps in response to the exceptionally ample acoustic—in which compositional skill, ample preparation and rehearsal, and immaculate playing combined to deliver real emotional heft. This was simply one of the finest of Mason’s works that I have yet heard, and it’s to be hoped that it will be taken up by other ensembles with this particular line-up of players.

|

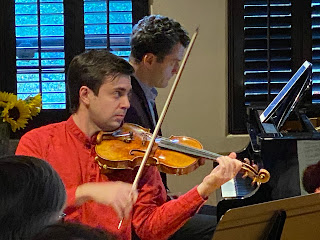

| Mozart in his early 20s, by Barbara Krafft. |

Unlike the Beethoven and the Mason, where all three instruments are treated as equals, Mozart’s Quartet very much highlights the flute, so that the work in effect becomes a miniature flute concerto. The opening Allegro was given extra dimension by the inclusion of its exposition repeat, making the movement occupy fully half the work’s total duration, but the highlight was undoubtedly the brief central Adagio.

Mozart confines his accompaniment for the flute’s long-breathed melody entirely to a delicate network of string pizzicati, and in the Dome’s wondrous space the sound of Ms. Mellis’s flute took on an Elysian, other-worldly quality that indelibly recalled Gluck’s “Dance of the Blessed Spirits” from Orfeo ed Euridice. A mere 34 measures, and it’s over, with the Rondo finale proceeding attaca. Mozart, at an even younger age than Beethoven when he wrote his Serenade, already knew how to leave an audience wanting more, as indeed did Ms. Tsan and her colleagues with this memorable concert.

---ooo---

100-Inch Telescope Dome, Mount Wilson Observatory, Sunday 22 May 2022, 3 p.m. and 5 p.m.

Photos: The performance: Todd Mason; Beethoven and Mozart: Wikimedia Commons.

If you found this review to be useful, interesting, or informative, please feel free to Buy Me A Coffee!

%20composers%20Jake%20Runestad,%20Frank%20Ticheli,%20and%20Tarik%20O%E2%80%99Regan;%20poet_lyricist%20Marcus%20Omari-1459.jpeg)