|

| l-r: Steven Vanhauwaert, Alma Fernandez, Cécilia Tsan, Ambroise Aubrun. |

REVIEW

Piano Quartet Masterpieces, Mason House, Mar Vista

John Stodder

For all but the most fortunate fans, most music we hear comes through a home stereo, car speakers or earbuds. No matter where it was recorded, we wrest it from that environment to ours. We might listen to the grandeur of Beethoven’s Ninth alone in bed, or an unaccompanied Bach violin sonata while staring through a windshield on the 405. It is easy to forget that before music became so portable, it was usually written for, and presented in, specific environments.

When we say “chamber music,” mostly we think of small ensembles, but the term describes the places where it was performed: not a “church, theater or public concert room,” according to the music historian Charles Burney, but instead a “palace chamber,” or in more egalitarian times, a private home.

A chamber is where over 50 classical music fans found ourselves on Saturday, April 9. Mason House, a small private home in Mar Vista, was remodeled a few years ago with the living and dining room combined into a performance space. Its most recent concert featured violinist Ambroise Aubrun, violist Alma Fernandez, cellist Cécilia Tsan and pianist Steven Vanhauwaert, who played Mason House’s Yamaha C-7 concert grand, with special German hammers to give a softer sound, ideal for chamber music.

What makes chamber music special is intimacy: the ability to hear the slightest change in how the players attack their instruments; how they navigate melodic passages that expand from one instrument to two, three or more, and fit their playing styles together. Chamber music is up close and personal. This concert was memorable in part because we in the audience could feel we were taking the journeys of these works along with each of the wonderful players, hearing nuances that would have been inaudible in a larger hall or outdoors.

|

| Todd Mason. |

|

| Mozart in 1782, three years before the composition of his First Piano Quartet. |

The Mozart performance exerted a steadying influence on audience emotions potentially inflamed by thoughts of war’s horrors. To be able to concentrate on musical details is therapeutic; like the string players’ bowing techniques and how they aligned them into one sound in unison passages, or the carefully modulated way in which Vanhauwaert would control his dynamics and presence within the ensemble.

Brown noted that contemporary audiences in 1785 were frustrated by this work’s “incomprehensible tintamarre of 4 instruments.” What I heard was delightfully comprehensible, and never dull. Mozart in his essence is the composer who presents his music as going in one direction—giving you every reason to think that’s where it’s going—and then plays beguiling games along the way to lead you to think something else might be happening, until you reach a point of surrendering any sense that you know where the piece was going—and then he takes you exactly where you expected in the first place, and you are grateful.

|

| Alma Fernandez. |

|

| Mahler aged 18 in 1878, two years after writing his Piano Quartet Movement. |

This piece walked a narrower path, from grief to melancholy to a kind of fearfulness that invoked our collective wartime moment. The quartet leaned powerfully into these emotions, their faces reflecting the mournful mood. It was a gift from the musicians to the audience to allow us to understand the depth of Mahler’s pain, to enable a catharsis. It is also a very different usage of the tools of chamber music, including the space itself and the intimacy it affords.

|

| Brahms in 1886, the year of the Third Piano Quartet. |

|

| Cécilia Tsan. |

|

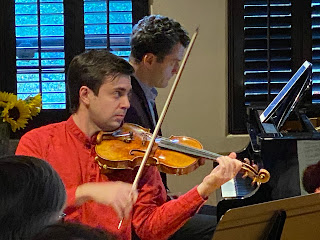

| Ambroise Aubrun and Steven Vanhauwaert. |

In this final movement, I recall feeling as if Papa Brahms had pulled his punches a bit. The first three movements had teed me up for the kind of climactic resolution of his concert hall classics. But the fourth movement seemed more… polite? And so it was. This “major statement” was not a symphony or concerto, but chamber music. We don’t want to alarm anyone. We’re home.

---ooo---

Images: The concert: Todd Mason; Mozart, Brahms: Wikimedia Commons; Mahler: Gustav Mahler website.

No comments:

Post a Comment