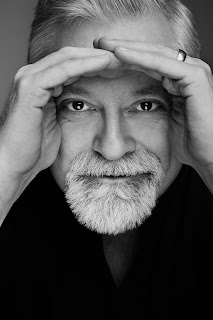

INTERVIEW: Daron Hagen

New York City, Chicago

ERICA MINER

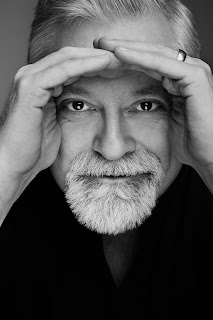

Versatile doesn’t begin to describe the creativity of Renaissance Man of Music Daron

Hagen. The Milwaukee-born award-winning composer, conductor, director, and all-around auteur has received commissions from top US orchestras. He has composed in almost every genre, including operatic roles and song cycles for some of the world’s leading vocal artists. His music has been performed worldwide. And he shows no sign of slowing down.

ERICA MINER: Congratulations, Daron, on your big news of the moment: Peermusic Classical’s just-announced publishing deal with Burning Sled Media to

publish some 150 of your works! How are you feeling about that?

DARON HAGEN: It was time to concentrate entirely on the work. At a certain point a person realizes they have fewer years in front of them than they have behind them. One begins to think of legacy. I wanted to make sure things were properly represented after I passed, and that my wife, Gilda Lyons, herself a very successful composer, wasn't saddled with servicing my catalogue, that it continued to create income for my children.

|

| Gilda Lyons |

EM: It makes perfect sense. What could be more exciting than to announce this news?

DH: It’s a mixture of excitement and relief. Excitement about the new adventures we can have—it’s always fun to have a new collaborator, right? — but also very comforting knowing my works will be taken care of. Inspiring and very humbling. Peermusic is a heck of a catalogue. They represent Ives and Tania León. I’m very honored to be in that company.

EM: You are, and so are they.

DH: [Laughs] Thank you, ma’am.

EM: Your body of work is glorious, also overwhelming, but I’d like to focus on your operas and operafilm, since that’s my area of expertise as a former Met Opera violinist.

DH: Yes, that’s a wonderful, simpatico place to start.

EM: First of all, Bandanna. What inspired you to join the ranks of opera composers who have set Shakespeare’s plays for the opera stage, in this case Othello?

|

| 'Bandanna' |

DH: That is quite a question, particularly from someone who knows the repertoire. It must strike you as hubris of me to have even attempted that particular story. The Venetian play is an incredibly durable piece of work, dramaturgically. I took it on for very personal reasons, not because Verdi did it but because I was coming out of a divorce. The idea of toxic relationships was much on my mind. The psychological situation, that distrust and self-loathing, all the things that come up when you’re going through such a terrible time. The ability to explore those feelings, to exorcise them through the work, inspired me to take on that subject. I had spent time as composer-in-residence at Baylor University in Waco and had gotten immersed in border issues. I felt strongly about the idea of setting Othello on the American-Mexican border as a way to indirectly talk about issues I cared a lot about. When it came to how to execute black and white, a binary understanding of good and evil is so limited.

EM: In this powerful operatic drama, you made a dramatic and philosophical decision, executed by your librettist Paul Muldoon, to “split evil into two forms: first, Jake (Iago) whose actual intentions were good, but whose effect was bad; and Kane, who was simply evil because, as Shakespeare explained, ‘because he could be.’ It requires a contemporary understanding of evil…Kane represents an excellent contemplation on people like Trump in our society.” Given the current perception that our democracy teeters on the edge, could you elaborate on this perspective?

DH: One of the things Shakespeare gave me by writing the play was a profound admonishment not to indulge in zeros and ones, that life is about the grey area between good and evil, decadence and innocence, trust and distrust. The human experience, the search for the divine, is a reaching out of the dark toward the light. These metaphors, going back 100s of years, are terribly fraught. They’re not fair. That we should call darkness a bad thing, light a good thing, but for lack of a better way to talk about it. We spend our lives, as Rilke said, the grey reaching for the light. That appealed to me. I constructed a piece all about unifying opposites. The highly literate language of the soul, coming out of Paul, expressed the articulate feelings of people who were inarticulate in their expressions in daily life. That’s the wonderful thing about opera—that a person who may be as poorly spoken as the wonderful Marlon Brando character in On the Waterfront, who, when he sings, can be as articulate as Shakespeare. That’s what opera can do. I wanted to give those people a voice that was profoundly articulate and yet jarringly in opposition to their lives. Feelings were profound and beautiful, but the circumstances in which they found themselves were perceived by the world as coarse. A longish answer, but that’s why I took it on. Illegal immigration and distrust, that there is no such thing as owning a person or land. This sounds very seditious, doesn’t it? I wrote the piece 20+ years ago, but I still care passionately about those issues.

EM: In some ways, they’re even timelier today. You’ve said, “The premiere of Bandanna was, of course, a disaster. The commissioners had no idea of what they had been given, and the production itself was terrible.” Would you care to comment?

DH: [Laughs] Only that I was a headstrong young man who wrote the piece I wanted to write instead of one that would have been appropriate for the occasion. That’s what I learned. Toscanini once kept yelling at a clarinet player and the player said, “Maestro, the clarinet player who can play that isn’t here today.” You don’t stage the perfect Rigoletto. You stage it for the people in the pit and on the stage that night. I didn’t write the perfect piece for that situation. I think you have to. I was singing so loudly, I was not listening.

EM: Yet the piece is very powerful. A youthful voice is also an effective one.

DH: Thank you.

EM: The European semi-staged premiere of Bandanna took place last June. It’s being revived in Italy?

|

| 'Bandanna' |

DH: In Italian, in Sicily no less, which is going to be really neat (six cities, planned for June 2023.) I’m very excited about that. Sicilians get that story! [Laughs] I’m very blessed to see the piece at least wear shoes, if not get some legs. You’re right, it is a passionate, youthful piece, written for 3 big, strong men who sing high all the time.

EM: Like Rossini’s version.

DH: Yes! Because of their machismo! The Bella Figura. Well and good, but that cuts down on the number of performances [Laughs]. It’s hard to find men that big.

EM: It didn’t stop Rossini, or you. You also said, “This is not my revival.” Somebody else is producing it. Will you be there?

DH: Yes. I have an 11-year-old and a 14-year-old. At the point where the revival takes place in a year and a half, my wife and I will go to Italy and have our first vacation together since starting a family, to see the show.

EM: Did someone approach you spontaneously and ask to do it?

DH: Not at all. I met Maestro Lorenzo Della Fonte when I was in residence at the Bellagio Center 20 years ago when I’d just written the piece. He was interested in it and never forgot it. He’s been trying to get this Italian premiere together ever since. It’s a tribute to him, his persistence and faith. There was a good portion of hubris in my taking on that subject, for a premiere in Austin, Texas. Finally, after 20+ years, succumbing to the humility of the maestro’s dedication to the work is another lesson to be taken as a composer from the experience.

EM: You are an amazingly prolific composer with a body of work that is astonishing in its scope, much of it described as, “Conceived, Composed, Directed, & Edited by Daron Hagen.” Let’s talk about your two latest operatic works in the emergent genre of composer-auteur operafilm. How do you define “operafilm?”

DH: Operafilm is neither an opera that has been filmed nor a film with people singing. As I am pursuing it personally right now, it is a work that issues from the composer’s visual and aural imagination manifested in film editing and sound design that mirror initial musical compositional impulses. When you experience it as an audience member, the beautiful collaborative result of great sound designer, director, editor, composer—all that beautiful team, can jell into a great film. But if that film is taken from the auteur, the Truffaut standpoint of issuing from someone’s own central vision and executed that way, it comes from the inside out. The inside vision collaborates with the people in the production and closes back in to open up on the screen, as opposed to a whole bunch of people centering on one document, trying to turn it into something else. Not better than staged opera— nothing will ever supplant staged opera and theater in my mind—but I’ve always thought visually, felt with words and music and looked at film critically. For me it wasn’t a leap to take a whack at it myself as Truffaut or Godard might. Ultimately operafilm is a very craft oriented, intimate thing, coming at the operafilm from the inside out as the opera composer rather than other people documenting what you’ve done from the outside in. I’m still working it out.

EM: It’s very profound, and a lot to unpack. Your Orson

Rehearsed (2018), a multi-media “dream” opera, has won multiple awards and was named “Opera News’ Critic's Choice” for August 2021. You’ve written: “Orson Welles’ heart has just stopped. We enter his mind in this moment, on the threshold between life and death…In the bardo Orson’s thoughts unspool as a stream of consciousness that loops back on itself, like a Möbius strip… he shuffles through his memories, loves, regrets, like a magician preparing for one last magic trick. Is he ready for what comes next?” That is certainly an enticing lead-in. What evoked these profound words?

DH: I grew up in the area where Orson Welles did, southeastern Wisconsin. I cotton to the way he was brought up. He represented an auteur whose brilliance I admired. The tragedy of his inability to play well with others doomed him to play alone. I found that profoundly moving. He was never a hero of mine. But among tragic artists he had a magnificent life, a life fully lived in the full swashbuckling sense. If you go inside the mind of a person teeming with ideas, you can be as teeming as want to be. Anything is possible in a mind that creative. The idea was to place the film in his head, which was the inside of a theater. His thoughts were in the nature of a live performance. I’ve been criticized by very intelligent opera producers who have said, well, that’s not a film because it contains elements of live performance. But a person who spent their life in the world of live performance, having seen the dream of a lifetime, wouldn’t they see their own thoughts as live performances?

EM: That would be a resounding yes.

|

| 'Orson Rehearsed' |

DH: A work like this becomes a Rorschach test for the way people think of what art and what consciousness are. The moment. A couple of years ago I was surprised to learn I had a congenital heart defect, and my aortic valve was deteriorating. I freaked out. I started thinking I should address this the same way that with Bandanna, the failed marriage, those are the issues I wanted to come to terms with. What would I think about if I knew I was dying? Because Welles died of a heart attack. What is the bardo like, that transitional place that Bandanna also spends a lot of time in, where you have to decide between whether you’re ready to go or not. That was the specific life event that inspired me to take on the project. Things I wanted to say before I no longer had another opportunity to do so.

EM: That fits right in with your definition of opera film.

DH: Yes, absolutely. What is the inside of theater but the inside of a mass collective conscious. You warm up in the pit of the Met and suddenly you are part of something bigger than all of us. Summoned, not by the genius of Verdi but the fact that he understood how to create a McGuffin, an excuse for us all to come together in a non-religious activity that was not Pagan. A pan-theocratic experience, more Platonic, more like what is outside in the dark, the things we see just the shadows of. We’re all afraid of the dark. Verdi went out into the dark, came back in and said, “You know there are monsters out there, they look like this,” and we’re all around our fire sitting in the Met and going, “Yeah, those are monsters, and he told us what they’re like. Maybe monsters are not quite so scary as we thought.” It’s the hero’s journey, Joseph Campbell. Can you think of anything more noble?

EM: Or immortal. It brings us all together on that plane. What is the premise of your most recent operafilm,

9/10: Love Before the Fall, (2021), which premiered just last year?

DH: It takes place the night before the Twin Towers. 4 people are having dinner in Little Italy. They all work in the towers. The next day they’re all going to die. The fall is the fall from the towers and the fall from grace, the Garden of Eden.

EM: And a literal fall.

|

| '9/10: Love Before the Fall' |

DH: Yes. It’s 4 “I am, I want” arias followed by a double proposal by 2 of the partners who’ve gotten together to propose to their partners on this special evening. They say yes and walk out into the night. At this restaurant is a bartender named Orfeo. On the radio is a woman named Eurydice, singing, and a violinist who works there named Charon who, as they’re about to leave, puts his hand out to each. They begin to realize they’re giving him more than a tip for the playing. And that’s where it ends.

EM: Staggering. I can hardly imagine the impact of everything you’ve brought together in that premise.

DH: Thank you. We filmed the restaurant sequences in April at an Italian restaurant in Chicago. We shot the cutaways at the bar. 4 cameras, a live performance. Like My Dinner with Andre crossed with Umbrellas of Cherbourg but more intense, as shot by Cassavetes. All the shots are very close in to these 4 people, framed by Charon coming up out of the subway, walking down Mulberry Street to work. He comes up out of hell. At the end, after he’s gotten his money, the people all go off to have a beautiful night, he walks down Mulberry Street and goes back down to hell.

EM: The next day dawns, and…

DH: They die.

EM: I can’t wait to see it.

DH: With Orson Rehearsed there were all sorts of interesting technical problems, a big theater. For this soundtrack, I was tired of fighting with the film guys and decided to loop the whole thing [Laughs]. So, I have all my singers looped to themselves. They feel absolutely secure having given their finest.

EM: It sounds brilliant. I’m dying to see what you’re cooking up next. Meanwhile, this has been a delight. Thank you so much, Daron.

Photo credits: Karen Pearson

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)