|

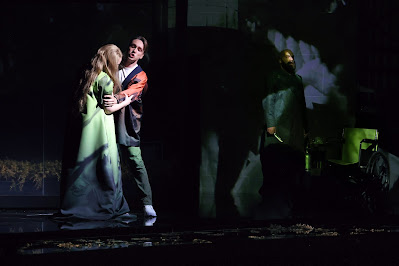

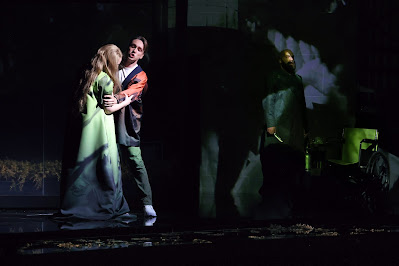

| Huw Montague Rendall and Samantha Hankey as Pelléas and Mélisande in Santa Fe Opera's production of Debussy's only completed opera. |

RODNEY PUNT

Introduction

|

| Wagner, 1840-1842. |

Richard Wagner’s early Romantic opera,

Der Fliegende Holländer WWV 63, written in 1840-41, has a ship captain fated to sail the seas until he is released from his eternal wandering by a faithful woman. With a stormy northern climate as its backdrop, Wagner created this foreboding work in primary musical colors. The journey from his Wagnerian darkness to Debussy’s delicate

Pelléas et Mélisande L 93, composed between 1893 and 1898, is a transition of qualities, from heavy and dark to light and lighter. Debussy’s ethereal work seems infused with touch-me-not action, its soft music drawn at times in barely discernible pastels.

|

| Claude Debussy. |

Performances of these two works at the Santa Fe Opera this summer, conducted respectively by Thomas Guggeis and Harry Bicket, suggested no obvious relationship between them. But there is an embedded developmental connection in their 60-year compositional timespan. Take a walk on successive Wagnerian operatic stepping-stones:

Tannhaüser,

Lohengrin, the tetralogy of

Der Ring des Nibelungen,

Tristan und Isolde, and reaching the last,

Parsifal. Wagner is ready to hand over the reins to Debussy, who admired and learned from both

Tristan und Isolde and

Parsifal and expressed his debt in

Pelléas et Mélisande.

---ooo---

|

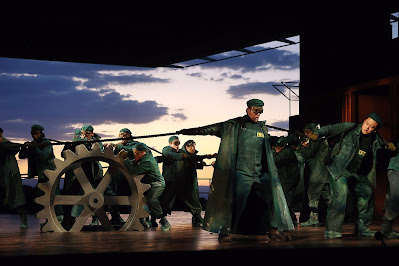

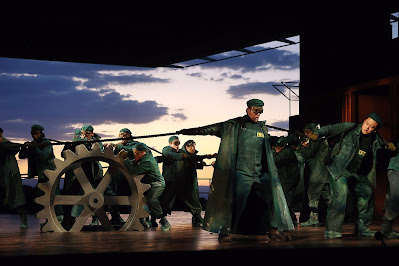

Nicholas Brownlee as the Dutchman, silhouetted against the Crosby Theatre's open backdrop

of New Mexico hills at sunset. |

Review of Der Fliegende Holländer, August 5

A Dutch sea captain is cursed to live forever, but allowed to come ashore once every seven years to look for a woman who will be faithful to him until death, which, with her steadfast pledge, will release his eternal curse, and let him die in peace. At sea, the Dutchman meets Norwegian Captain Daland, open to any means of gaining wealth, and whose best bargaining chip happens to be his unmarried daughter, Senta. She, in turn, has been avoiding her most ardent suiter, a local hunter boy named Erik, who is madly in love with her. The Dutchman gives his portrait to Daland who later gives it to his daughter, who is immediately taken with the Dutchman, at which point the end game of this work is set in motion.

|

| The men of Santa Fe Opera chorus at sea. |

Originally conceived as a short opera by Wagner, the final product, still short by Wagnerian standards, is fleshed out with a sailors’ chorus at sea and, as balance, a similar women’s spinning chorus in the port city. These two choral numbers provided the best opportunity this season to hear the phenomenal choral work of Santa Fe Opera’s young artists, by a good measure the fullest choral presentation of the five-opera season.

|

| Daland (Morris Robinson). |

Bass-baritone Nicholas Brownlee’s voice filled the Crosby Theatre stage with the dark and foreboding prognostications of his Dutchman’s fate. In the past seven years, this Dutchman has amassed a king’s ransom of lucre with which to pay a dowry for the faithful wife he seeks to release him from his eternity at sea. Bass Morris Robinson’s Daland, in craven greed, grasps the opportunity to accept the Dutchman’s dowry for Senta. Their bargain scene was well choreographed, with Brownlee and Robinson on opposite sides of the stage giving ominous portent of their pact.

Another townsman, the grief-stricken Erik (tenor Chad Shelton, replacing the originally scheduled Richard Trey Smagur), emotes genuine anger and panic at losing Senta, the village girl he had loved for so long. (A tenor’s loss at love is relatively rare, an operatic role reversal symbolic of the normal order of this story being out of whack.)

|

| Senta (Elza van den Heever) with the women of Santa Fe Opera chorus. |

Soprano Elza van den Heever’s Senta, a good match vocally for Brownlee, has in some ways the most interesting stage treatment here. She is made up to look plain, almost butch, suggesting a possible twist on her own motivations to avoid the usual village female role of sewing contentedly for a lifetime at home. She may intuitively embrace the sacrifice of her own life to escape physical love inherent in her expected role as housewife... or may secretly be excited to trade the insignificance of sea village life for a larger good, something more important, that motivates the spontaneous jump off the cliff after the Dutchman has set sail.

When he realizes that the Senta he has fallen in love with, and agreed to marry, must die as part of the curse on himself, the Dutchman has last-minute qualms and tries to escape again on his ship in order to save her life. But Senta, true to her promise, and perhaps to her secret pact with herself not to marry, still jumps off the local cliff, at last releasing the Dutchman to break the curse and himself die in peace and deliverance.

---ooo---

|

| Netia Jones' production design for Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande |

Review of Pelléas et Mélisande, August 3

As mentioned, Debussy’s innovative score owes a musical debt to the spiritual world of Parsifal and the love-triangle of Tristan, yet, in his search of another musical path, Debussy resisted the seductive influence to directly imitate Wagner’s style. This work looks to the Far East, notably Japan and Indonesia, for its coloration as well as a certain delicacy. The East’s pentatonic scales and gamelan hues—along with unusual instrumental combinations and the use of parallel triads, and unorthodox 7th and 9th chords—produced exotic, hothouse sounds that gave the composer an original musical voice perfectly suited to the play (and one that would go on to influence composers like Stravinsky and Ravel).

|

Susan Graham as Geneviève

in the Santa Fe production. |

Debussy’s ethereal, indeterminate music, with Maeterlinck’s touch-me-not drama of the mind, has challenged stage directors for generations since the work’s 1902 Paris premiere. For Los Angeles audiences, the 1995 staging by Peter Sellars at LA Opera in the Chandler Pavilion tried to break the obscurantist mold by tailoring the drama to a modern setting of homeless lovers on a beachside in Malibu. Alas, the intriguing concept had them groping on a dim stage with fluorescent lights inconveniently shining in the audience’s eyes.

|

| Golaud (Zachary Nelson). |

Santa Fe Opera’s production avoided such extraneous statements. Stage director Netia Jones, also responsible for scenic designs, costumes, and projections, let the action tell the story and the music provide much of the inner tension. She avoided the kind of distracting high concept production that had Sellars smothering the pastel subtlety of this fragile work of Debussy, which needs to quietly work on an audience’s inner emotions.

|

| Yniold (Kai Edgar). |

The protagonists forged an ideally strong and idiomatic team. In the tenor role of the fated Pelléas, the English lyric baritone Huw Montague Rendall sustained just the right ethereal French nuance in accent and stage manner. Samantha Hankey’s more open and generic soprano did not have quite the French nasality that would have made this pairing ideal, but she did convey Mélisande with a fatal purity that chimed with Debussy’s unchanging musical motif at her every entrance. Baritone Zachary Nelson’s increasingly unhinged Golaud added, step by step, to the inexorable fatalistic power of extracting jealous revenge.

Seasoned mezzo-soprano Susan Graham provided a sympathetic and resonant Geneviève to soften the tragedy, along with Raymond Aceto’s Arkel, even as the two were powerless to stop the unfolding tragedy. In the role of the boy, Yniold, was the sweet Kai Edgar. The misuse of his character by Golaud to spy and report on a potential love scene is one of the more tragic moments in this work. Ben Brady’s Physician reinforced the role of helpless bystander to tragedy. All in all, this was a Pelléas et Mélisande that did not force the action, but let the story unfold naturally.

|

| The lovers about to meet their doom at the hands of Golaud. |

---ooo---

Crosby Theatre, Santa Fe Opera, 301 Opera Drive, Santa Fe, NM, Thursday, August 3, and Saturday, August 5, 2023, 8:00 p.m.

Images: Wagner and Debussy: Wikimedia Commons; the productions: Curtis Brown.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.